14. Filtering of Data in GMT¶

The GMT programs filter1d (for tables of data indexed to one independent variable) and grdfilter (for data given as 2-dimensional grids) allow filtering of data by a moving-window process. (To filter a grid by Fourier transform use grdfft.) Both programs use an argument -F<type><width> to specify the type of process and the window’s width (in 1-D) or diameter (in 2-D). (In filter1d the width is a length of the time or space ordinate axis, while in grdfilter it is the diameter of a circular area whose distance unit is related to the grid mesh via the -D option). If the process is a median, mode, or extreme value estimator then the window output cannot be written as a convolution and the filtering operation is not a linear operator. If the process is a weighted average, as in the boxcar, cosine, and gaussian filter types, then linear operator theory applies to the filtering process. These three filters can be described as convolutions with an impulse response function, and their transfer functions can be used to describe how they alter components in the input as a function of wavelength.

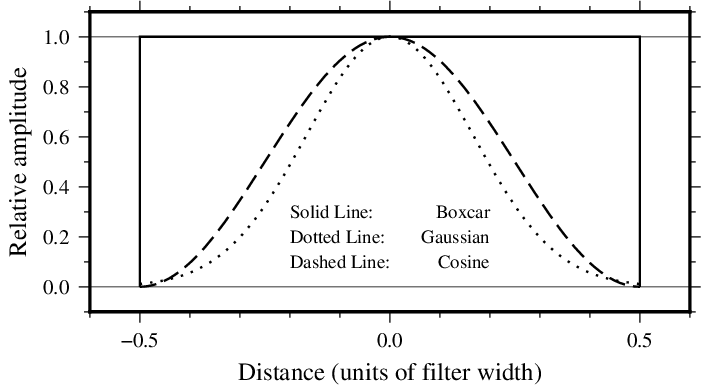

Impulse responses are shown here for the boxcar, cosine, and gaussian filters. Only the relative amplitudes of the filter weights shown; the values in the center of the window have been fixed equal to 1 for ease of plotting. In this way the same graph can serve to illustrate both the 1-D and 2-D impulse responses; in the 2-D case this plot is a diametrical cross-section through the filter weights (Figure Impulse responses).

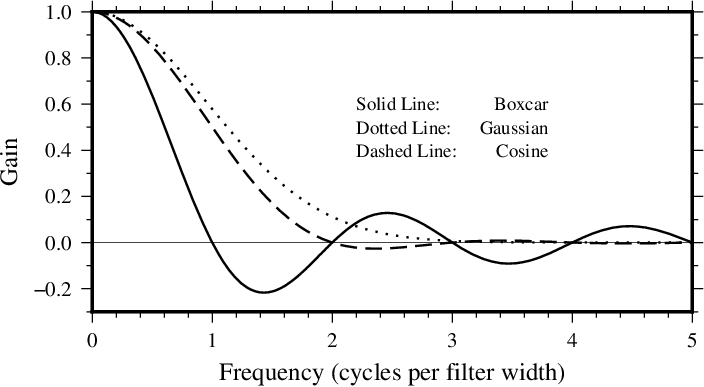

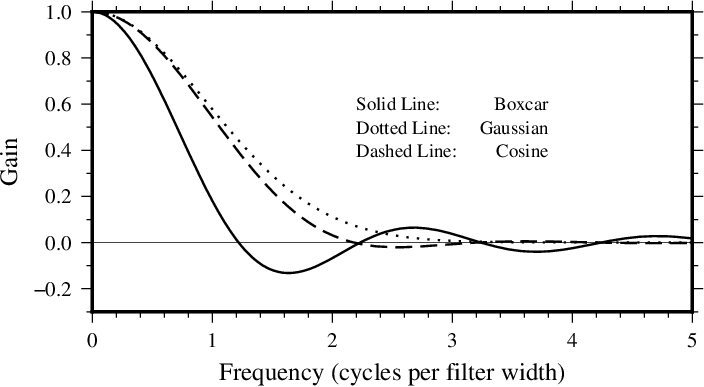

Although the impulse responses look the same in 1-D and 2-D, this is not true of the transfer functions; in 1-D the transfer function is the Fourier transform of the impulse response, while in 2-D it is the Hankel transform of the impulse response. These are shown in Figures Transfer functions for 1D and 2D, respectively. Note that in 1-D the boxcar transfer function has its first zero crossing at f = 1, while in 2-D it is around \(f \sim 1.2\). The 1-D cosine transfer function has its first zero crossing at f = 2; so a cosine filter needs to be twice as wide as a boxcar filter in order to zero the same lowest frequency. As a general rule, the cosine and gaussian filters are “better” in the sense that they do not have the “side lobes” (large-amplitude oscillations in the transfer function) that the boxcar filter has. However, they are correspondingly “worse” in the sense that they require more work (doubling the width to achieve the same cut-off wavelength).

One of the nice things about the gaussian filter is that its transfer functions are the same in 1-D and 2-D. Another nice property is that it has no negative side lobes. There are many definitions of the gaussian filter in the literature (see page 7 of Bracewell [30]). We define \(\sigma\) equal to 1/6 of the filter width, and the impulse response proportional to \(\exp[-0.5(t/\sigma)^2)\). With this definition, the transfer function is \(\exp[-2(\pi\sigma f)^2]\) and the wavelength at which the transfer function equals 0.5 is about 5.34 \(\sigma\), or about 0.89 of the filter width.

| [30] | R. Bracewell, The Fourier Transform and its Applications, McGraw-Hill, London, 444 p., 1965. |